|

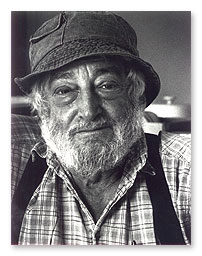

Don Bell was a writer, a book collector, and most recently, a columnist for Books in Canada. He passed away in Montreal on March 6, 2003. Don's legendary book Saturday Night at the Bagel Factory won the 1973 Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour. The column below is the ninth and last of "Founde Bookes" that he wrote for Books in Canada. April 2003. Volume 32, No. 3 Don Bell's Founde Bookes The Blue Notebook

My colleague Manfred, très simpatico--I prefer to call him colleague rather than competitor even though he and his wife Nancy ran the other secondhand bookshop in Sutton--had been having a rough time last winter; serious health problems made it difficult for Manfred to ply his other trade as bicycle mechanic, they lost one of their three daughters, and business was not always brisk in their Ex-Libris shop around the corner from the dépanneur. There were times when Nancy and Manfred could hardly afford cat food or wood to heat their home. Which is why I offered to help when Manfred showed me a slim volume that he had picked up at the Concordia Book Sale called The Blue Notebook by the Russian writer Emmanuil Kazakevich, a writer popular in the old Soviet Union but little known in the West. The book was brought out in translation in 1962 by Progress Publishers of Moscow. It's a novelized account of the atmosphere and dialectics while Lenin and his Bolshevik followers were hiding in the forest near the Finnish border in the months leading up to the October 1917 armed uprising, led by Lenin. The plot--if it could be called a plot--revolves around Lenin's blue-covered notebook laying out the ideology of the New Socialist Order. This notebook was the fodder for his famous work, The State and Revolution. Manfred had high hopes for the book even though it was the 1969 second printing. A listing of the same edition on the addall.com website which he printed out had the book posted at $2495.34 (U.S.). It was probably a scarce book of special interest to collectors of Russian literature; no doubt the most precious book he and Nancy had on hand. One of my contacts from book-scouting days in Paris is a high-end dealer from Boston specializing in European literature, especially Russian. If The Blue Notebook could bring in just half of its listed value, Nancy and Manfred would be able to buy enough cat foot and wood to last several winters. "We'll go fifty-fifty," Manfred offered. "No, just a bottle of wine, if you feel so inclined." "You're a gentleman, Don, but not a very good poet." So I emailed the Boston contact, whose clients include many well-off academics and affluent Hollywood celebrities. "Sounds interesting," John Wronoski of Lame Duck Books politely e-mailed back, "but I doubt I'd be able to sell it anywhere near that price; good luck anyway." Before sending out more feelers, I realized it would be wise to check addall.com again and other websites, which I foolheartedly neglected to do the first time around. Guess what. It turns out that the $2495.34 listing was a mistake, a typo: Akran Fine Books in Chevy Chase, Maryland was offering the same edition as ours for a measly $24.95. Elsewhere, a flawed copy was posted at $8 and others in "very good condition" made it up to $15 or so. Whoops, sorry about that "fucked-up decimal point", as one of my helpers called it. That was the end of Don the Bookman's patronizing Good Samaritanism. As for Nancy and Manfred, they're a proud couple (Manfred was a fighter pilot with the U.S. air force for 20 years, Nancy a home-care worker)--somehow they survived, although they're still struggling to keep afloat, like all of us, in the not-so-fast lane of secondhand books. One client-less day while I was minding my own business in Librairie Founde Bookes in the premises of the old barbershop on the main street of Sutton, I suddenly had an itch to read Kazakevich's book that caused the confusion, this false hope, and offered to buy it from them -- what the hell, why not? -- "not for $2495.34, but how does 15 bucks look to you, Nancy?" So here it is in front of me. The cloth cover of course is cerulean blue with the title in silvery lettering and Kazakevich's name encrusted in black on top. The endpapers are unique in that they carry a description of the book and some useful background on the author, information such as one would normally find on a dustjacket, which this book never had. We're told that Lenin kept the original blue notebook while he was abroad (in Switzerland, Germany and Sweden) in 1916-17. It was filled with quotations from Marx and Engels and extracts from other Socialist philosophers as well as Lenin's own ideological meditations. While he was hiding in a haymaker's hut in the forest near the Finnish border and being hunted by agents of Kerensky's Provisional Government, Lenin wrote to an editor: "If I am knocked off, I ask you to publish my notebook, Marxism and the State (which became The State and Revolution). It is bound in a blue cover." Kazakevich himself, we learn from the endpapers, was born in the Ukraine in 1913, the son of a teacher. He was a poet, novelist (known especially for The Star, also published in translation by Progress), and translator into Yiddish of Pushkin, Lermontov and Mayakovsky. He died in 1962. The Blue Notebook was his last work. "He was a passionate traveler, a hunter, a crack shot, a top-notch driver, the life of the party, witty and full of fun. Moreover, he was a truly courageous soldier," wrote his contemporary Alexander Tvardovsky. Eagerly, I pitched into The Blue Notebook in the shop, but found it hard to get into at first, perhaps because customers came in asking for French-English dictionaries and books on cabinet-making, but more likely because the design of The Blue Notebook was off-putting--too much type crammed onto each almost margin-less page, certainly not aesthetically appealing as books go, not easy on the eyes. A few days later I had another go at it during a long sit-in at a Tim Horton's and wolfed down Kazakevich's 105-page proletarian outing between munches of an explosion de fruit muffin and slurpfuls of Hortonesque decaf ... and was suddenly surreally transported to the hut in the forest outside Razliv where Lenin and his fellow-revolutionaries plotted to overthrow the provisional government and set up an unalloyed Marxist state with the backing of Russia's overworked, underfed masses. Diogenes said "Most men are a finger's breadth from being mad." This is how his opponents might have seen Lenin, but reading Kazakevich's character study, the Great Leader impresses us as being possibly the sanest person in pre-revolutionary Russia, a man at once highly-intelligent and well-educated but who also had a practical sense and who saw how Marxism could be applied to the everyday life of the common Russian. It's hard to square Kazakevich's Lenin with the tyrant who established the Cheka political police force in 1917 and whose opponents were imprisoned or murdered, but historical accuracy may not have been Kazakevich's intention. Lenin is often seen through the eyes of impressionable Kolya, the 13-year-old son of Lenin's friend and fellow militant Sergei Alliluyev Yemelyanov (oh, those Russian monickers!). Disguised as a Finnish haymaker, Lenin is attuned to the forest--plants, animals, food. Lenin's meal in the forest is described in loving detail (I started to salivate when I read this)..."He drew a hunk of bread out of a bag, a bottle of sunflower seed oil, a bunch of spring onions and a few cucumbers..." Elsewhere, Lenin expresses strong culinary preferences--"fish soup without ruff or at least perch is not worth making." Lenin is portrayed as an admirer of children, a defender of women's interests, a modest and self-effacing person, as charming and forgiving--in short, the book is an attempt to humanize Lenin, to depict him as sensitive to the delights of the empirical world and the needs and sufferings of ordinary people. Even his love of the working class stems from his love of individual workers, not from attachment to the working class as an abstract entity-- "He could not stand those socialists like Plekhanov who worshipped the 'proleteriat', swore by the 'proleteriat' but who had no warm feelings for Vanya, Fedya, Mitya, Ivan Ivanovich or Pelageya Petrovna, who did not believe in their common sense and did not care a brass kopek for them. For such socialists 'proleteriat' had gradually turned into something amorphous, vague, immaterial, it had become a formula, dry as a skeleton, and hollow as an idol." On the surface, The Blue Notebook reads like a straightforward hagiography, no more interesting than odes to Mao and other revolutionary leaders. But the work was written in 1961, long after Lenin had died, and it can be read more charitably as a critique of his inhumane successors, especially the paranoid and cold-blooded Stalin. The discussion of State and Revolution in Kazakevich's work also hints at things that went drastically wrong after Lenin. The state may be a temporary necessity but it is supposed to "wither away." Even the temporary state is described as "a state where there will be no place for highly paid officials, where all the officials will be elected and replaceable at any time, where the functions of audit and control will be fulfilled by the majority of the people." The gap between the ideal and the reality would have been obvious to readers of The Blue Notebook. Maybe the book after all is worth two-and-a-half grand. May I end this with an anecdotal afterword: I'd been scribbling, as mentioned, at Tim Horton's in my own blue notebook, which contained notes for other Founde Bookes columns as well. On leaving, I chucked a plastic bag with the two notebooks (or so I thought) in the front seat of the car and started to pull away, then paused for a second to double-check the bag. A moment of pure panic! The Bureau En Gros Hilroy lined blue notebook was missing. Your favorite columnist was too out-of-breath in this 20-below weather to go bursting inside; however, looking through the window we noticed one of the Tim Hortonites grabbing something off the floor and bringing it toward the counter, or was he about to toss it in la poubelle, to be absorbed in a mush of sour cream and honey muffins? I blasted the horn maybe 30 times but it obviously couldn't be heard through the plate glass; finally, a Good Samaritan (this column is all about Good Samaritans) pulled up in her car and asked the out-of-breath writer what the problem was. "The ... the b-blue n-notebook!" I stammered, pointing. She went inside and retrieved the precious item. "Here you are, Sir. Are you all right now?" "Yes. Merci, madame. Vous êtes très gentille." We all have our Blue Notebooks, don't we? From each his or her own literary explosion, to each his or her own notebook. You can be a Leninist or a muffinist, in the long run it all amounts to the same. This month: Time with my Father by Daniel Bell |

||

|

| Downtown Montreal Guide | Old Montreal Guide | Guide to Eating Out | Walking Tours |

| Urban Landscape | Guide to Literary Montreal | Montreal Vintage Photos | | Montreal Links | Montreal Jazz | www.vehiculepress.com © Véhicule Press, All Rights Reserved |